Observing animals underwater has obvious limitations. In most cases, we can't really see what's going on from the surface, and even with SCUBA diving, we can only stay underwater for a limited time. This is a problem for marine researchers trying to follow our ocean animals, especially when the most basic of questions to ask is -

"Where do they go?"

Even just for basic information on animals, we need to know where they go, when they go there, and what they’re doing. Unlike mapping where stationery species like plants and corals are found, determining distributions for moving animals is more difficult, particularly in the aquatic environment where our ability to observe mobile animals is severely limited.

Many studies of marine animals rely on 'tag and recapture' techniques

to monitor their movements. Using this technique, an individual is

caught and a unique identifier is recorded. The identifier can be a

tag attached to the animal OR a unique natural feature, such as a photograph of spot

patterns in leopard sharks, or whale fluke patterns. Individual details are

recorded, the animal is released and we wait to see if it is caught again.

These

techniques are relatively low cost and, when conducted on a large scale over

long periods, can provide great information about populations and their behaviours.

It is often used for monitoring populations of birds, turtles and marine

mammals.

BUT, the tag and recapture technique has a number of drawbacks:

|

| A sevengill shark with a unique ID tag attached to its dorsal fin |

BUT, the tag and recapture technique has a number of drawbacks:

- It relies on re-capturing an animal, which is often up to chance (e.g. shark studies on average have a 5% recapture rate)

- If tags are used, the tags can fall off

- There is no information on what the animal is doing in between the periods of capture or sighting

- We might never see the animal again.

So how do we find out where these animals are going, if

we can’t be in the water with them 24/7?

Enter tracking technology.

In this series of posts, we’ll look at some of the

tracking technology that we use for our OIQ projects, starting with acoustic

tracking.

Part 1 – Passive Acoustic Tracking

What is acoustic tracking?

Acoustic tracking (or acoustic telemetry) uses tags attached to animals that emit short sounds, or ‘pings’ at a set frequency. Unlike light, sound carries well underwater, so it can be used to locate an animal if they are within a reasonable distance. There are 2 main types of acoustic tracking – Passive and Active.Passive Acoustic tracking

Passive acoustic tracking consists of

2 components:

The transmitter is attached to an animal. This can be attached

externally or by implanting it inside the animal using surgical procedures.

Each tag is individually coded with a unique identification number, like a bar

code, which it randomly transmits between pre-set intervals e.g. between 60 -180

seconds.

These are permanently fixed in the marine environment. They are commonly attached to moorings held on the sea floor.

1. The Transmitter (or tag)

|

| Transmitters come in a range of different sizes suited for different sized animals |

|

| Yoda overseeing a number of transmitters ready for deployment |

2. The Acoustic Receiver (or listening station)

These are permanently fixed in the marine environment. They are commonly attached to moorings held on the sea floor.

|

Example of a mooring system for receivers. Here, we used the extremely high tech method of old car tires filled with cement. A split pin system (on steel poles) assists with changing the receivers over.

< Watch to see the transmitter and receiver in action!

When a tagged animal comes within range of an acoustic receiver, its ID number is detected and, along with the time and date of the detection, is stored on the receiver. A tag’s detection range can vary depending on its signal strength and the environment it is deployed in, but as a rough guide, the animal will be detected once it moves within 400-500 m of the receiver.

How it works

< Watch to see the transmitter and receiver in action!

When a tagged animal comes within range of an acoustic receiver, its ID number is detected and, along with the time and date of the detection, is stored on the receiver. A tag’s detection range can vary depending on its signal strength and the environment it is deployed in, but as a rough guide, the animal will be detected once it moves within 400-500 m of the receiver.

We

periodically retrieve these receivers to download the data and obtain the detection

information. The battery lives of the tags these days can be more than 10 years, allowing for long-term studies. For details on how the receivers are deployed,

visit the Save our Sea Foundation (SOSF).

Acoustic telemetry can tell us:

- How often particular individuals visit that area

- How long they stay there for

- If the animal shows a daily pattern in its movements

- If there is a seasonal pattern to its movements

OIQ use passive acoustic tracking on a

number of our projects. For example, for our Osprey Reef project, we have

attached acoustic tags to more than 50 sharks (whitetips, grey reefs and

silvertips) and have monitored their movements in and around the reef since 2008, using an array of receivers. An array is a series of receivers

setup over an area designed to determine the movement of

animals over a reasonably broad area. This can be at and around a reef (or series of

reefs), like the Osprey study (see below), or throughout coastal bays and estuaries as seen

in our sevengill shark studies in Australia and South Africa.

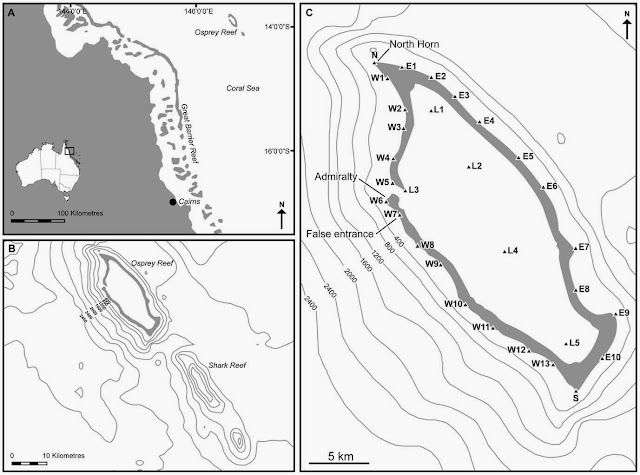

An example of an array of acoustic receivers at Osprey Reef, Coral Sea (Image A and B). Panel C shows the depth contours (in metres) around Osprey Reef,the acoustic receiver array forming a ring around the perimeter of Osprey Reef, and the 5

receivers within the lagoon. Triangles represent receivers. North Horn,

Admiralty and False Entrance are the shark tagging locations.

Using acoustic tags at Osprey Reef, we have found that most of the sharks remain not only at Osprey, but they have certain sites on that reef they prefer. For example, whitetip reef sharks spent all of their time around a small area where they were tagged (approximately 3-5 km home range). Our open

A co-operative monitoring approach

Acoustic tracking using an array is expensive to set up and maintain. Even large arrays can normally only cover a portion of an animal's range. Generally, studies of highly mobile marine species are limited by the amount of receivers that can be deployed i.e. areas they can cover with receivers.However, in some parts of the world many studies deploy acoustic receivers and with many receivers comes wide coverage. Dedicated programs such as the Ocean Tracking Network and The Australian Animal Tagging and Monitoring System, cover large large stretches of coastlines (out to the continental shelf) with receivers. These programs allow animals from one study to be detected on receivers deployed for other studies, thereby supplying coarse information on larger-scale movements.

And if the animal moves too far?

Then we need to find the right technique for the right job. For animals with very large ranges, such as tiger sharks and turtles, acoustic tracking can be limited in its scope to obtain detailed information of the tracks taken in large scale movements. Thankfully we have another technology up our sleeves – satellite tracking.Stay tuned for our next post!

UPDATE:

If you liked this post, you may be interested in the other posts in the 'Guide to tagging and tracking' series

No comments:

Post a Comment